Why caches

Over the years, the gap between the throughput of the processor and the throughput of main memory has widened. Programs cannot make use of higher processor speeds or a large number of cores if they are constantly waiting on expensive memory accesses. The solution chip designers have come up with is to place a hierarchy of caches between the processor and main memory. Caches closer to the processor are smaller and use faster memory technology, e.g. SRAM. Caches further away from the processor are larger and slower, and they act as a backstop for caches above them. The goal is to keep frequently accessed data as far up the memory hierarchy as possible and minimize the number of calls to main memory.

Cache organization

In general, a cache memory consists of \(S\) sets, each with \(E\) cache lines. On one end, when \(E = 1\), we have a direct mapped cache, where each set has just one line. On the other end, when \(S = 1\), we have a fully associative cache, where we have just a single set containing all the lines. Caches in today’s CPUs are usually somewhere in between, e.g. 4-way set associative, where each set has 4 lines. Below shows three types of caches side by side, courtesy of Wikipedia.

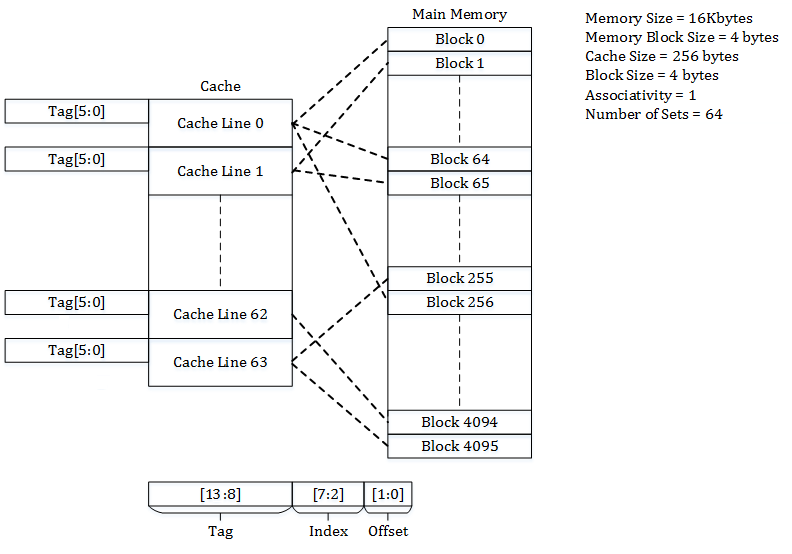

Direct-mapped cache

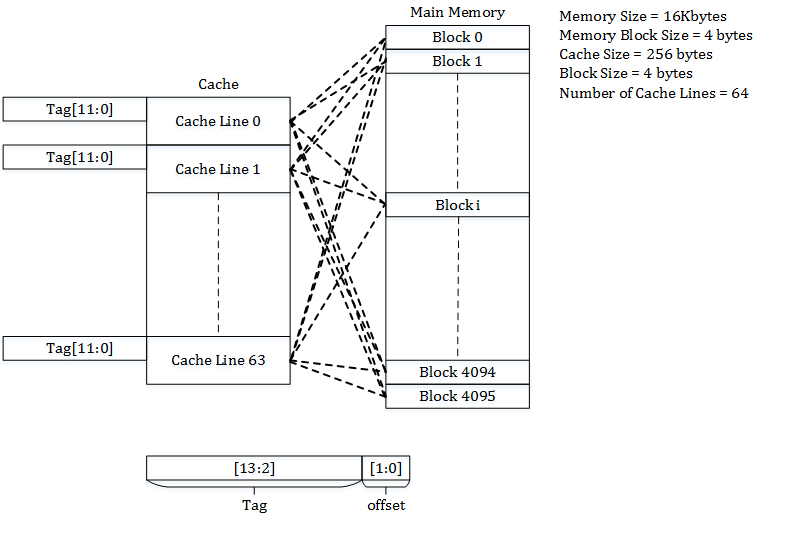

Fully associative cache

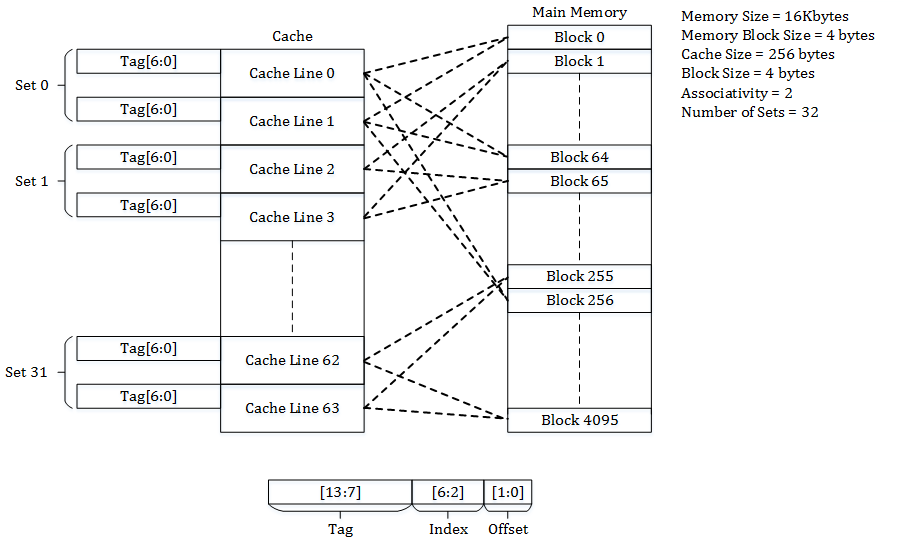

Set associative cache

Each cache line contains a valid bit, \(t\) tag bits, and a data block of \(B\) bytes. The valid bit indicates whether the cache line should be used. The tag bits come from part of the memory address we want to store, and it uniquely identifies the line in the set. The data block stores the actual bytes that we want cached.

When want to access an memory address in the cache, we break it down into three parts: the tag, the set index, and the byte offset. With these three pieces of information, we can identify the entry in the cache, if it exists. We use the set index to locate the set, the tag to locate the line in the set, and the byte offset to locate the data in the block.

For example, the Intel Pentium 4 processor has a 4-way set associative cache of 8 KiB total, and each cache line is 64 bytes. So there are a total of 8 KiB / 64 = 128 cache lines, divided into 128 / 4 = 32 total sets. With a 32-bit address space, we need 5 bits to identify the set, 6 bits to identify the byte in the 64-byte block, leaving 32-(5+6) = 21 tag bits to select the line in the set.

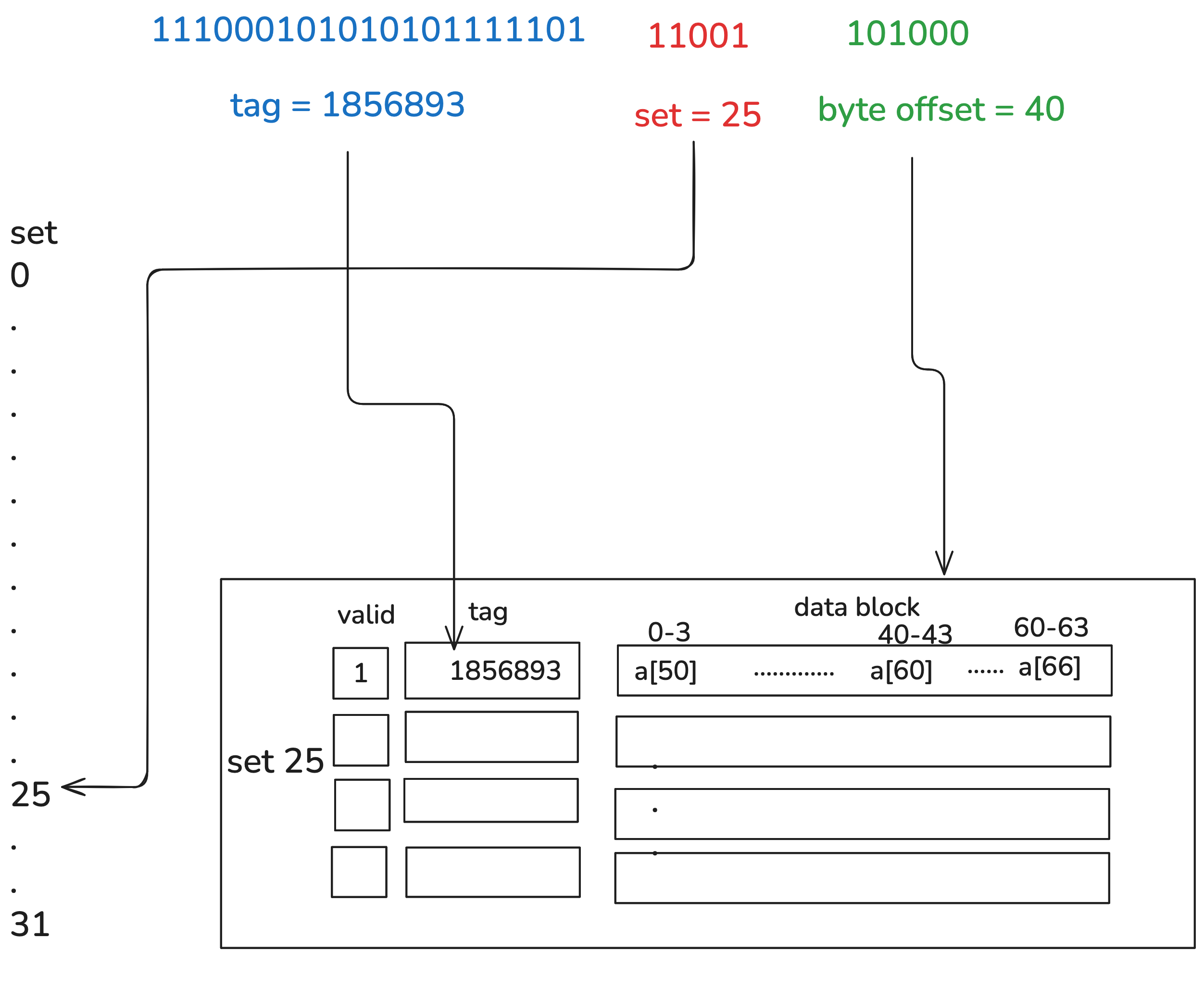

To see this in action, suppose we have a 100-element array of floats, and we want to read the 60th element, i.e. a[60], which happens to be at memory address 0xe2abee6a. Below is a diagram to show this memory load.

To read the array element, we:

- index into set 25 of the possible 32

- iterate through the 4 cache lines and look for the one with tag 1856893

- if it doesn’t exist, create an entry with tag 1856893, and load 64 bytes of data into the cache line, with

a[60]at byte 40; if it exists, we just load the 40th byte!

Conflict misses

Conflict misses arise when we repeatedly access memory addresses that map to the same set, which causes repeated cache evictions and thus fetches from lower memory levels, increasing the latency. The most extreme example of this is if we have a direct-mapped cache and try to compute the dot product of two vectors that happen to be spaced number of sets * lines per set apart. We call this the critical stride.

float dot_product(std::vector<float> &x, std::vector<float> &y) {

float sum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < x.size(); ++i) {

sum += x[i] * y[i];

}

return sum;

}

This means each element in x and the corresponding element in y will be mapped to the same set, so the cache line gets replaced over and over again in a hot loop.

This is also why the set index are the middle bits rather than higher bits: when scanning an array, consecutive elements can be placed in a maximum number of sets in a round-robin fashion rather than mapping to the same set, which causes thrashing.

Cache coherency

Typically not all caches are shared. For example, each processor usually has its own L1 cache. Cache coherency refers to keeping individual caches in sync with each other. One thing to note is that this is not a database where we can tolerate stale reads, i.e. non-strong consistency. Each cache must contain the latest data or else be invalid, in which case we fetch from main memory.

The most commonly used protocol for cache coherency is known as the MESI protocol. MESI allows all cache lines to be in one of four states:

- Modified: the cache line has been modified and is not in sync with main memory, but no other core has this cache line

- Exclusive: the cache line is in sync with main memory and no other core has this cache line

- Shared: the cache line is in sync with main memory and another core also has this cache line

- Invalid: the cache line is invalid because another core has changed it

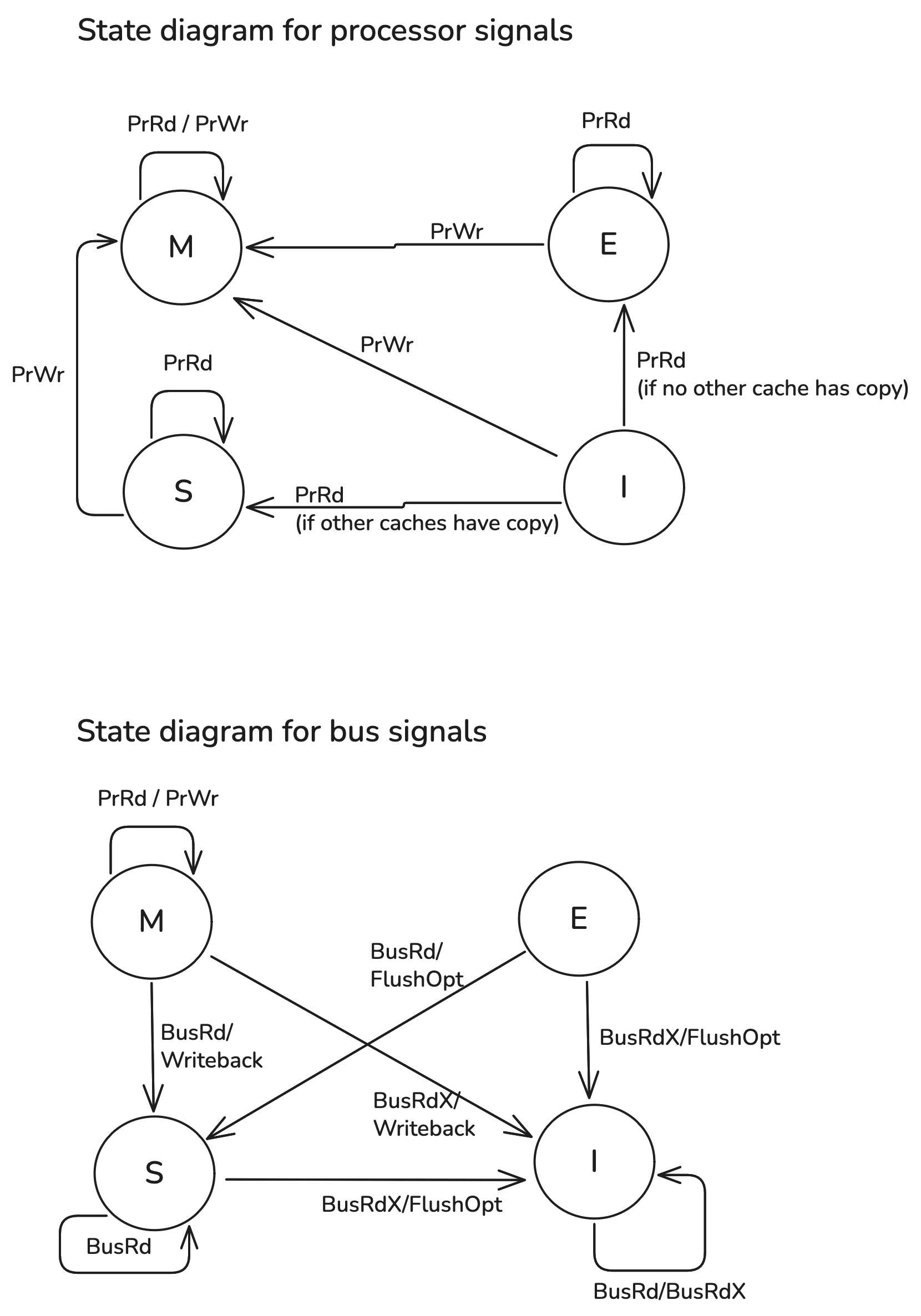

When the a core issues read and write instructions, the other cores are notified through a signal on a shared bus indicating how the state of their own cache lines should be modified. There are two types of signals: processor signals and bus signals. Processor signals are sent by the processor to its cache. Bus signals are sent by a cache to other cache(s) on the shared bus, and are intercepted by what are known as “snoopers,” who watch for bus transactions.

Processor signals include the following:

- PrRd: the processor wants to write to the cache

- PrWr: the processor wants to read from the cache

Bus signals include the following:

- BusRd: another processor wants to read a cache line present on this processor

- BusRdX: another processor wants to write a cache line it doesn’t have that is present on this processor

- BusUpgr: another processor wants to write a cache line it has that is also present on this processor

- Writeback: a cache line should be written to main memory

- FlushOpt: a cache line should be transferred on the shared bus

Below is what happens at each state when these signals are received:

If cache line is Modified:

- If it receives PrRd or PrWr from the processor, it remains in Modified state since no other cache has this line. It will just read or write to the local cache.

- If it receives BusRd/Writeback, it means another core wants to read the line. In this case, the current core will write the line to main memory and send it to the requesting cache, then transition into Shared.

- If it receives BusRdX/WriteBack, it means another core wants to write to the line. Similar to the previous case, the current core will write the line to memory and send it to the requesting cache. But since we know the other core will modify it, so we know the current copy will be stale and thus transition into Invalid.

If cache line is Exclusive:

- If it receives the PrRd signal, it remains in Exclusive state.

- If it receives the PrWr signal, it transitions into the Modified state.

- If it receives BusRd/FlushOpt, that means another cache wants to read from it. In this case it will send the cache line on the bus and transition into Shared since the cache line is now shared between processors.

- If it receives BusRdX/FlushOpt, it means another core wants to write to the line. It will supply the line on the bus to the requesting core and transition into Invalid. In this case, there is no memory write since the current line is unmodified.

If cache line is Shared:

- If it receives PrRd, it remains in Shared.

- If it receives PrWr, it will change the cache line and thus become Modified. In this case, since it was in the Shared state, the cache line is also held by other caches, who will have to discard it.

- If it receives a BusRd, it remains in Shared.

- If it receives BusRdX/FlushOpt, we know another cache wants to write to it, so we send the line and transiion to Invalid.

If cache line is Invalid:

- If it receives PrRd, it transitions into Exclusive if no other cache has this line and Shared otherwise.

- If it receives PrWr, it transitions into Modified.

- If it receives either BusRd (another core wants to read) or BusRdX (another core wants to write), nothing changes since the current line is invalid. In this case, the requesting core is broadcasting the request to all the caches, and either another recipient core will respond or nobody responds, in which case the requesting core will need to read from memory.

Below shows a walkthrough of what happens when three cores try to read/write to the same cache line. The sequence of operations are: 1. processor 2 reads, 2. processor 2 writes, 3. processor 1 reads, etc.

local request P1 P2 P3 generated bus request data supplier

0 initial - - - - -

1 R2 - E - BusRd main memory

2 W2 - M - - -

3 R1 S S - BusRd P2

4 W1 M I - BusUpgr -

5 R2 S S - BusRd P1

6 R1 S S - - -

7 R3 S S S BusRd P1/P2

General tips for optimizing code

Below are some very general tips for optimizing the performance of your code.

- Aim for good temporal locality, accessing the same data/functions close together in time. This applies to both data and instructions, as CPUs typically have separate caches for data and instructions. This will make good use of data that has already been recently cached.

- Aim for good spatial locality, accessing data/functions close together in space/memory. Each data access loads a 64 byte cache line, so if you’re reading an object that lives close to another object you’ve previously read, chances are it’s been loaded into the cache.

- Try to avoid data structures with inherently non-sequential access patterns like linked-lists, trees and hashmaps. These tend to jump around between random addresses in memory, incurring cache misses. When accesses are not predictable, other optimizations such as cache prefetching and branch prediction also don’t work as well. For the same reason, whenever possible, try to avoid dynamic allocation, as the heap can become fragmented and your allocations can be spread out across a large range of addresses.

- Try to avoid accessing data structures in a non-sequential pattern, e.g. iterating through a 2d array by column first.

- Don’t use Big O as a proxy for how fast your program runs. Sometimes an algorithm with a slower time complexity can beat a faster alternative simply because it utilizes the CPU cache more effectively. For example, a O(N) search through an array may outperform building a hashmap with O(1) lookup for certain workloads.

References

- Agner Fog’s optimization manuals

- What Every Programmer Should Know About Memory

- Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective - Bryant & O’Hallaron

- Cache placement policies - Wikipedia

- MESI - Wikipedia